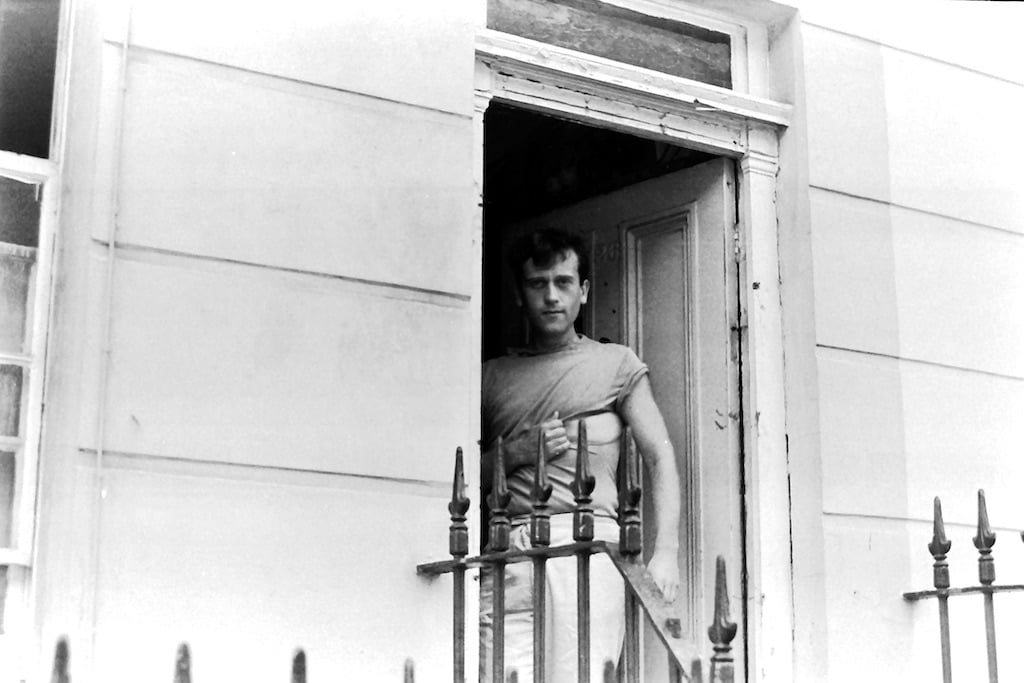

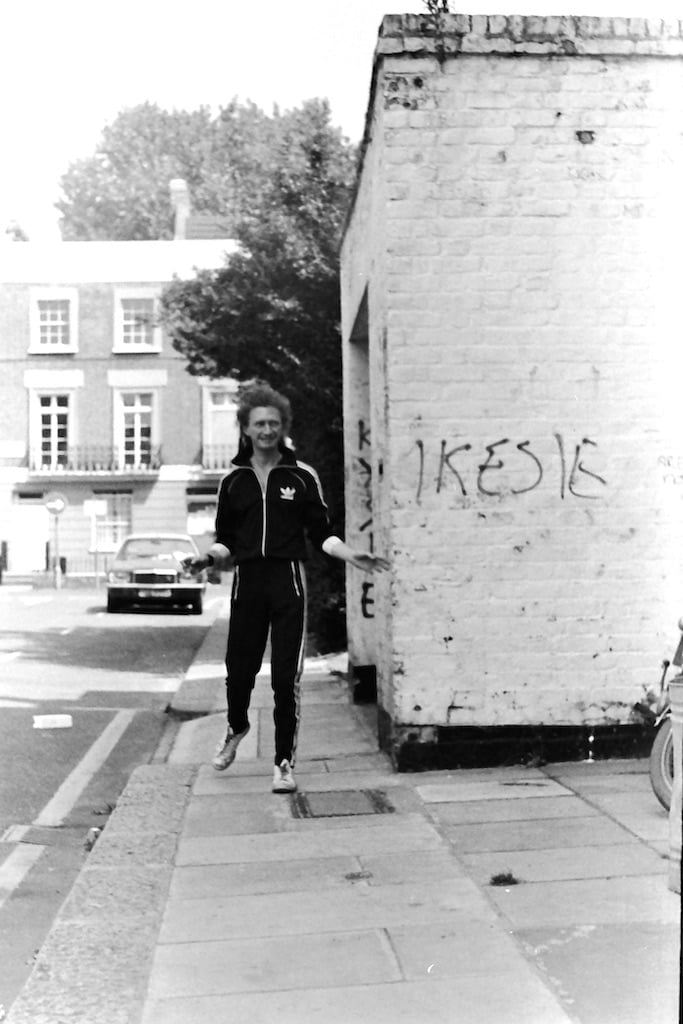

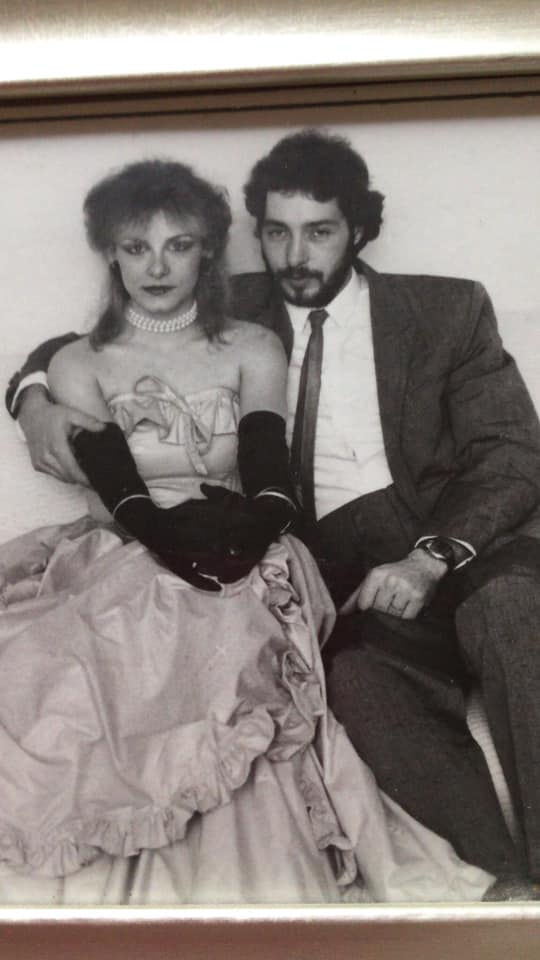

The featured photo above of me (John Cook) is by Susan Andrews. It is from the time in the early 1980s when we went to 'inspect' Moys factory at the end of Carol Street. At the time there was a campaign called "What's Moys is yours", led by Plume, to get the empty Moys building repurposed for local community use.

Draft Abstract 25 March 2025 (planned work)

Squatting is occupying property without permission (this is one definition). There is a gap in the squatter movement literature with respect to London in the 1980s. This work fills the gap. Indeed, an examination of the activist literature from the early 1980s (e.g. The Crowbar) indicates that South London, at the least, had a politically active squatter network/subculture. However, the myth of the squatter movement as ‘autonomous activists’ has become problematic and needs revision because it “has become a dominant ideological paradigm in the movement. … The myth is dogmatic, exclusive, and so powerful that movement activists are regularly unable to go beyond the image and its limits” (Kadir, 2014, p. 23). Consequently, not only does the literature gap need filling but care must be taken when mapping out the London in the 1980s squatter network/subcultures in terms of myth and memory (see also van der Steen et al., 2020; Cook, 2024).

Following a brief review illustrating the gap in the literature, we explore the Kadir ‘autonomous activists’ myth/assertion, by moving from the general to the specific, as follows.

First, we examine contemporary accounts from the time (which have their own bias, e.g. The Crowbar) and in so doing map out the squats in London in the early 1980s. This first approach also provides a view of the ‘various ways in which squatter networks/subcultures were constructed, understood and utilized as a cultural medium at a particular historical juncture’ (Worley 2017: 18, paraphrased). This is my 'existence proof', in that the map demonstrates that 1980s London squatter network did exist and that the associated subcultures could have occured.

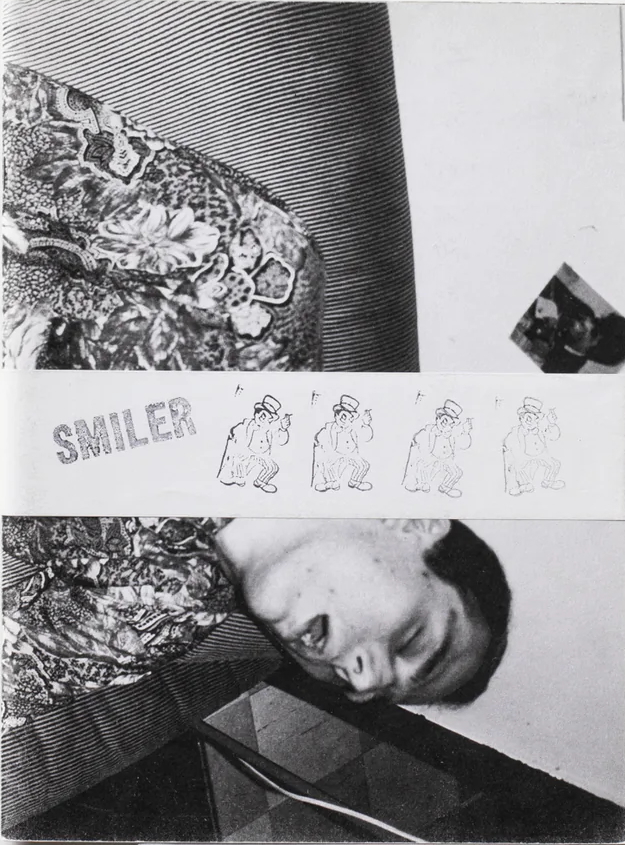

Second, we provide several autoethnography-biographical or photographic accounts of members of London squatter network/subcultures in the early 1980s where the focus of the subcultures was post-punk music (e.g. Cook, Trancentral), photography (e.g. Smiler, Wettre), theatre groups (Plume & Fish) and art (Hornsey College of Art, and associated people e.g. Smiler, Neal Brown, Becky Weeks); there were overlaps, and some subcultures/individuals were involved in activism. Care is taken to eschew myth and over interpretation; e.g. by drawing on Cook's cold case approach (Cook, 2024) and the Kadir's (2014) Amsterdam case.

We conclude by suggesting that squatter subcultures in early 1980s London were extensive and fluid. Various questions arise. What were the reasons for overlooking squatters in 1980s London in the literature? Where they not deemed politically active enough? Was there an over emphasis on the Crass-like anarcho punk set ups in the punk scholarship literature? Was the North London network seen as too arty? Were there individuals that did not represent themselves in written form? What impact did the influx of 'ethnic-minorities', changing demographics and women have?

Contributions and comments welcome (see end for contact)

Below I have included some texts, media and links to give you a flavour of where some of the cases are heading

The Crowbar newsletters

Produced initially at 121 Railton Rd, Brixton, by a predominantly anarchist group

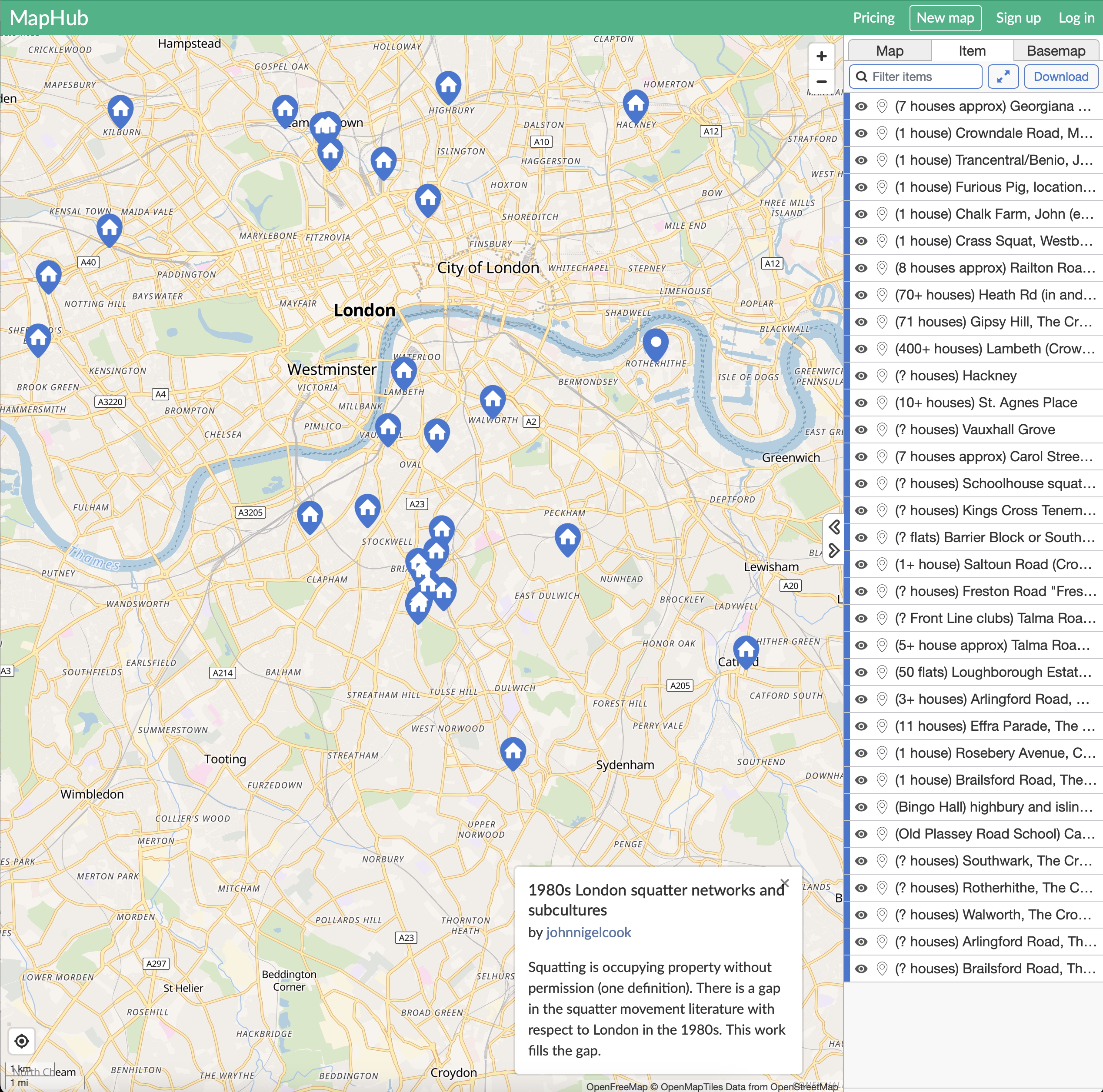

Evolving online map

I am using MapHub which is a free, 'online mapping tool that allows users to create interactive maps with markers, routes, and other features, and offers options for sharing and collaboration, built on OpenStreetMap data and open datasets'. Click here for the project's evolving map or https://tinyurl.com/rjkdwkxt (note: it may take a while to load up! Also, the info box may hide South London!). A screen shot of an early version is shown below (I started creating this map 19 March 2025). This is my 'existence proof', in that the map demonstrates that 1980s London squatter network did exist and that the associated subcultures could have occured.

Screenshot 2025-03-27

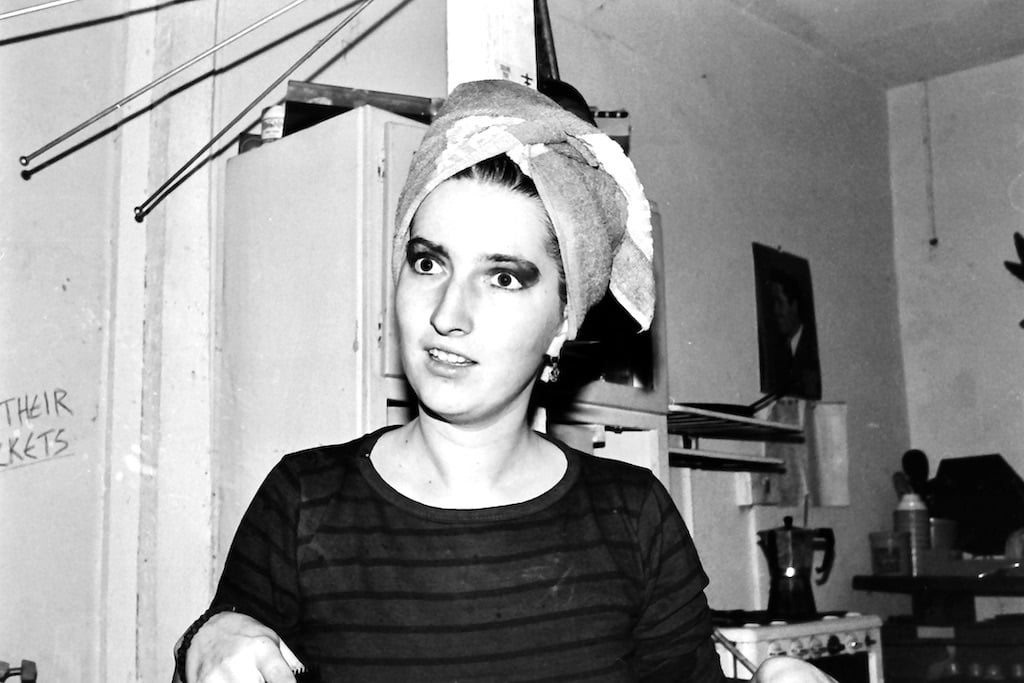

Halvdan Wettre's photo portraits of squatters in North London, 1980-82

Below are 10 photos by Halvdan Wettre, mostly Georgiana Sreeet, Camden Town, all are taken in North Lodon, 1980-82

"The most widespread and damaging lie is that squatters can squat in people's homes while the real residents spend months in court trying to get them out. This is a highly emotive issue and a hugely popular media story, but it is also untrue and totally distorts the notion of squatting in the popular imagination: the Criminal Law Act 1977 provides ample protection for a residential occupier and squatting other people's homes is a criminal offence" Guardian 16 Sep 2011

The Georgiana Street squats became a housing cooperative in the 1990s and are reportedly in better repair than local council housing stock.

John Cook's autoethnography extracts

Here is the first diary entry that I had made since my move to the squat at 26 Georgiana Street (Camden Town, London); the entry is dated 25th August 1980 (just over a month after the move):

“Life in London is different. It took me a day or two to feel secure(securer!). There are a lot more drugs than is normal for me, something I find enjoyable. Get on with the other three, at one point especially Rog, then particularly Tim. We seem to understand one another ??”.

(Personal diary entry, 25th August 1980).

From the above, I can say that there is some fragility on my part: this was a big thing for me. My Mother was not happy I was squatting. Clearly weed/marijuana was being smoked, and enjoyed, and I am getting on with the guys I was squatting with. Jump forward 4 years I am still squatting and playing in indie bands. Below is an extract from Cook (2024) where I look at my time with cult indie band Strawberry Switchblade.

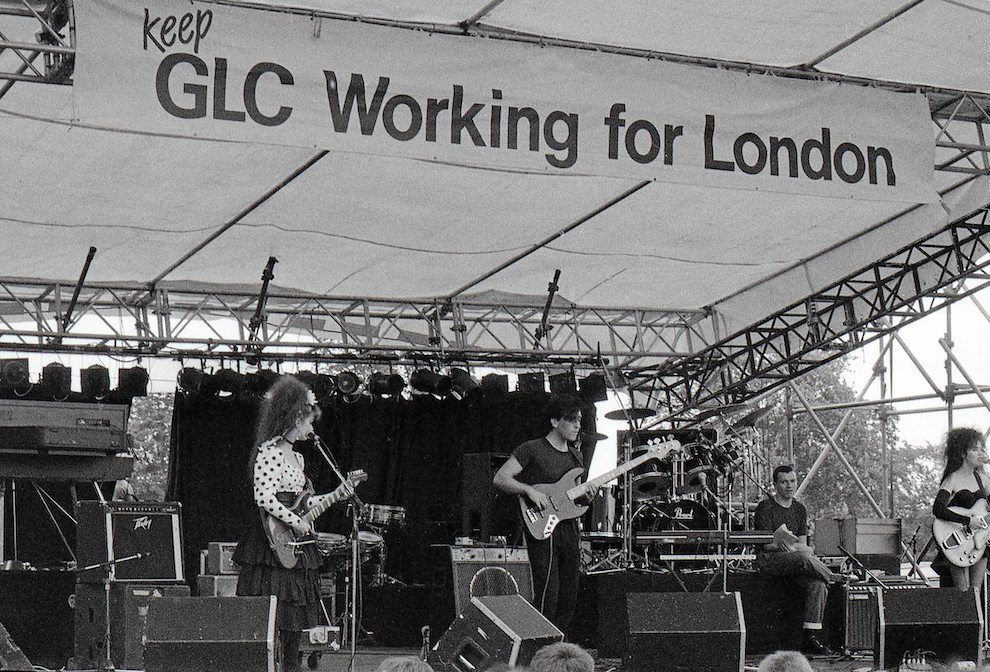

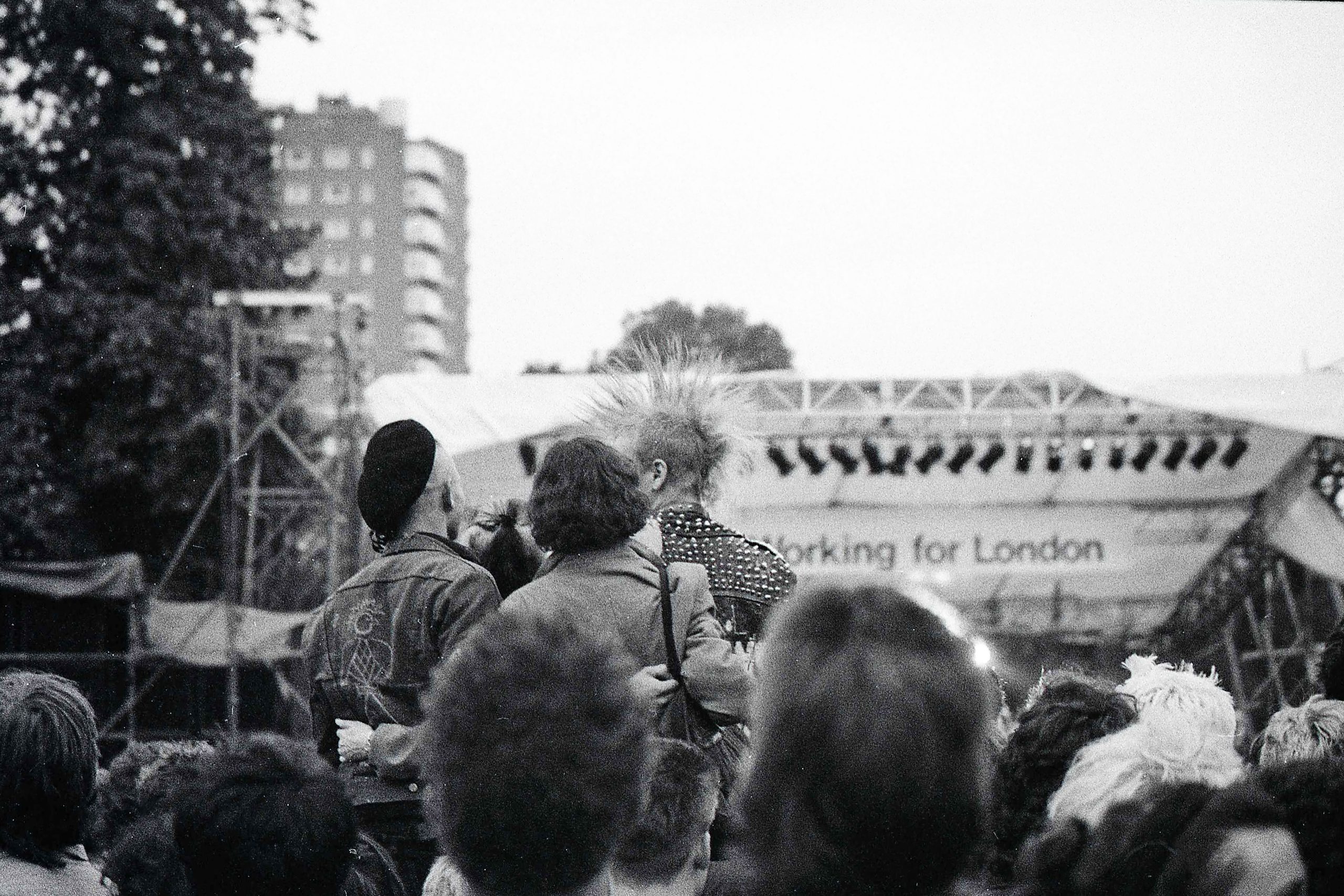

"The band co-manager said to me after the Brockwell Park gig in a band meeting: ‘Well John, you just about got it together’. But Rose and Jill told him off and said, ‘he did good!’ I was a bit bemused and did not respond. Forty years later, this now seems like a harsh comment, given the aggro we had been exposed to on the day and the fact that this was a one-off gig without the usual Simon and Roy but with a drum machine. It certainly made me feel discomforted and uncertain ... Eventually, in the late 1980s I got into other types of paid employment. Was this change due to the events described above? Probably yes, the writing was on the wall for this 1980–85 indie music episode of my career. The music industry was a precarious form of employment back then. My son is currently working as a musician and things seem to have gotten worse".

I had by 1985 fully tested the myth of the 'punk DIY' attitude, i.e. picking up an instrument and just having a go. As a self taught musician the myth held true but wore thin.

Below. Gavin Watson's previously unseen photos - John plays Brockwell Park festival with Strawberry Switchblade - London 1984. I particularly like the second photo, which for me shows the passing from punk to post-punk. Gavin sent me his rejected play from the time, which is semi-autobiographical.

An ill-fated Angels One 5 performance at the UK Brixton Riot Reconciliation Concert, 1982 (? tbc). I played bass (John Cook). I think the Brixton riots were still raw and we were an all white band. I remember Cressida Bowyer our lead singer being fearless. I also remember that we got a ‘thank you’ letter from the organising committee. This provides insight into the tension between the local community, which was predominantly of Afro-Caribbean descent, and Angels One 5, an all white indie band.

The wider context is this case provides an example of the band’s struggle to get a second single out on any indie label; it also provides links via Jimmy Cauty, the guitarist. Cauty went on to form an trance, hip-hop, sample inflected band with Bill Drummond called the KLF. Drummond re-mortgaged his family home to set up their own indie record label. The KLF made millions of pounds and had various international hits and burnt a million pounds on the Isle of Jura. The KLF were supreme at generating myths, some of which may or may not have been true. Trancentral (a.k.a. the Benio) was the band's studios. Despite the grandiose lyrics of "Last Train to Trancentral", the Trancentral was in fact Cauty's residence in Stockwell, South London, "a large and rather grotty squat"; it had a studio in the basement, a large green dentist chair in the living room and was the venue for many brilliant parties.

Cressida Bowyer formed Disco 2000 with “Mo”. Between 1987 and 1989, Disco 2000 released three singles on the KLF Communications label.

Smiler: Mark Cawson (Smiler) and artist/writer Neil Brown

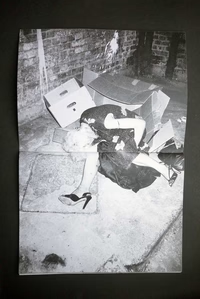

"Go Smiler’s. Kings Cross. Tenement squats. Full scenic Oliver Twist look. Smiler and camera. I stay my girlfriend’s squat. Sex". Neal Brown

"Diane. Smiler took pic of her to show her. Diane (Two Weeks Before Her Overdose and Death), Kings Cross (circa 1983)". Neal Brown

(Confirmation needed that the above photo is Diane; need to check with Neal when 'Camera Squat Smiler' text was written).

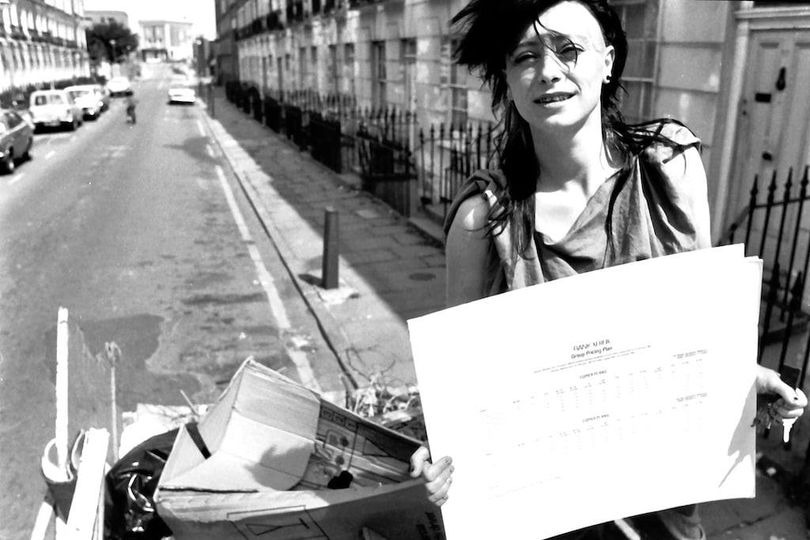

The answer is of course "yes". For example, Lorraine was one such person who was reluctant to write online about her experience and had lost all her photos from the day. She did, however, provide (personal communication) the above photo and this message below. Lorraine from No 29 was part of our (i.e. No 26: Roger-RIP, Tony, me, others) support network. She bailed us out from time to time, as did Julie and Les-RIP at No 17, as did Plume on Carol Street around the corner.

Hornsey College of Art, associated people and squats

Becky Weeks and her brother Dominic (photo by Halvdan Wettre)

"Several elements contributed to the eruption of rioting in Brixton in 1981. In parallel with the development of Brixton’s Afro-Caribbean community, the racism it faced from the police, and the resistance this provoked, the other crucial factor was the heavily squatted nature of housing in the area, which had the effect of producing a proliferation of radical and liberation projects. Mass squatting in the Brixton area was a product of a combination of a failed planning project, a spike in homelessness and the emergence of the modern squatters’ movement in 1969". (online article written April 10, 2021)

The above is a good update on the common myth of who exactly squatters were/are: "The myth of the militant, organised, confrontational, anti-authoritarian, articulate, and 'autonomous' activist - usually represented as a thin, white man in his late teens of early twenties, wearing a balaclava and throwing stones from the roofs of squatted houses or confronting the police has become a dominant ideological paradigm in the movement. The myth itself serves as a beacon that attracts many activists to the movement and fulfils unresolved identity needs" (Kadir, 2014, p. 23).

However, the retrospective online article helps with our mapping: "In St Agnes Place, squatters had first moved into empty houses in 1974 – some of the buildings had been unoccupied for 14 years. By December 1976 over 100 people were squatting there. In January 1977 over 250 police had arrived at dawn to preside over the demolition of empty houses, although the demolition was stopped within hours by a hastily initiated court injunction by the squatters. These houses remained squatted for decades, to be finally evicted and demolished in 2005". online article

Research approach

Based on my trial study called 'A cold case from 1984' (Cook, 2024) I will report each case in terms of the following types of evidence: (i) diary entries, (ii) articles from the time, (iii) personal recollections and first-hand accounts. Evidence types (i) and (ii) function here as more desirable as they provide a view of the ‘various ways in which squatter networks were constructed, understood and utilized as a cultural medium at a particular historical juncture’ (Worley 2017: 18, paraphrased). Photos and other media from the time under investigation are valuable as memory prompts (type iv evidence). Evidence type (iii) provide a narrative but are subject to the limitations of forensic psychology and how we forget and modify memory over time (Louw 2015). I will avoid the trend whereby some of the the squatter movement literature is bookended by highly theorised, top-down accounts that seek to the squeeze squatter movement into pre-designated paradigms.

About John

Maybe people will wonder where I am coming from? I don't have a particular axe to grind. I am from West Yorkshire, have a chip on each shoulder and so am well balanced! For my research approach (see above) I draw on work by a Professor of Modern History from the University of Reading called Matthew Worely, who specialises in twentieth-century British culture and politics. Nothing is totally objective, but I aim to be transparent and intend to view all perspectives. So for the record: at the time under study I was an insider squatting on Georgiana Street (Camden Town, London), at the time I played in indie bands, later I became a research Professor of Education who typically got assessed as 3-4* in REF-type peer review assessments (4* is the highest) & my view is that 'subculture' remains a useful if amorphous concept. I see myself as an outsider academic, indeed my 3 blog posts explain that, as a gamekeeper's son I have travelled a long way.

Contact

johnnielcook@gmail.com

Overview of academic profile and outputs