In Part 2 I mentioned that I am convinced that the creative people that I encountered in the 1980s really shaped me and helped me to become a successful, but outsider, research Professor and a good father. As a Gamekeeper's Son I think I have travelled a long way. Well let's see. UK Academia is a bit of a middle class affair, so how did I get on?

I have been lucky to meet people and see places from around the world. Some photos from these trips are here. This is a period of my life when I should have thought more about my carbon footprint! Nevertheless, for me they represent special moments with academic colleagues and the people you meet when you are a guest in another part of the world. The culture and beautiful scenery stick in my mind; and in fact these are the focus of the pictures in this part of the Blog. But these photos also remind me of the amazing opportunities that I have been given to talk about my research to the diverse, global, academic community. As a Gamekeeper's son I have travelled a long way! Hence below I have added some text to explain a small part of what I was up to.

Academic travelogue outside the UK (not very Green I know)

Below I list academic trips to conferences to present papers or give invited talks, or to attend meetings. This list excludes Brussels & Luxembourg many times for EC meetings; and repeated meetings for research and development projects in Bremen, Karlsruhe, Innsbruck, Paris, and many more locations across Europe.

USA, Washington - 1995

Portugal, Lisbon - 1996

Japan, Kobé - 1997

Canada, Montréal - 2000

New Zealand, Palmerston North - 2000

Australia,Wollongong & Melbourne - 2001

Finland, Tampere - 2001

New Zealand, Auckland - 2002

Switzerland, Lugano - 2004

Ireland, Maynooth - 2006

Palestine Territories - 2006

Spain, Alicante - 2006

Canada, Banff - 2007

Canada, Vancouver - 2007

Ireland, Dublin - 2007

Germany, Dresden - 2008

USA, San Diego - 2009

Germany, Garmisch-Partenkirchen - 2009

Slovakia - 2009

Germany, Mainz - 2010

Macedonia, Ohrid - 2010

Germany, Bremen - 2011

USA, New Orleans - 2011

Italy, Palermo - 2011

Portugal, Estoril - 2012

Canada, Vancouver - 2012

Germany, Paderborn - 2012

Germany, Augsburg - 2012

USA, Washingtom - 2013

France, Vercors - 2013

Cyprus, Paphos - 2013

Indonesia, Bali - 2014

Romania, Sinaia - 2015

Spain, Toledo - 2015

Hungary, Budapest - 2016

Malta, Vallatta - 2016

Canada, Vancouver - 2016

First I need to explain why I feel I am an outsider, on the edge of the academic community

In episode 2 of 'Part 2 - London in the 80s' I bring in forms of Capital to foreground the issues raised in the my own apparent ‘cultural capital deficit’. Bourdieu argued (I am simplifying it, link to my paper on this) that the cultural habits and dispositions of someone's family are fundamentally important for success and represent a resource, a form of cultural capital. In contrast to cultural capital, Putnam describes another form of 'capital': social capital is the creation of social networks between socially heterogeneous groups; examples are choirs and bowling clubs. Indeed, an Education Committee’s report points out that one reason for this deficit is a “lack of social capital (for example the absence of community organisations and youth groups)”. For me squatting in London in the early 80s was like getting a second degree, but this time in music, art and culture. In terms of the groups of people I met in the early 80s: I would never have normally had the chance to interact with such a diverse set of people. I can even draw a comparison with the coffee houses in the 1600s (link to my paper on this), which were, in fact, crucibles of creativity and communication because of the way in which they facilitated the mixing of both people and ideas. As the poet from that time Samuel Butler put it, “gentleman, mechanic, lord, and scoundrel mix, and are all of a piece”, the implication being that people from different segments of society and skill sets could meet and network. Indeed, members of the Royal Society, England’s pioneering scientific society, frequently retired to coffee houses to extend their discussions. Consequently, I believe I gained strong social capital and more importantly agency from my time in Camden Town. I am convinced it helped me in later years to productively deal with the stress and strain of being a researcher.

However, I am afraid I agree with this quote: "We don’t know how many working-class academics there are, as figures are not collated, but my experience as one tells me they are underrepresented ... some hide their background, changing their accent, dress and taste". (Guardian, 2018). I am slightly ashamed to say that I hid my northern roots and accent when I joined academia, instead choosing to project the arty, musician, middle class values I had picked up from rubbing shoulders with such people whilst squatting, living in housing coops and generally being an indie musician. Indeed, when I mentioned this to one academic colleague he agreed and said he got fired from the BBC for being too working-class! I confess I do have an axe to grind, and I have evidence ...

Unfortunately, this is not just stereotypical thinking. Conway (1997) argues that entrance to education, paths and decisions within education and school achievement is related to social class and cultural capital, and thus reproduces social inequalities. The paper concludes that the ‘middle class’ in Britain struggles to maintain social positions, but this ‘segment’ of people also have the resources to climb upwards in society. Whereas the ‘working class’ seem very hesitant, traditional, without the necessary resources for social mobility. Indeed, The UK Government’s Education Committee’s June 2021 report “The forgotten: how White working-class pupils have been let down, and how to change it”, highlights how “White British pupils eligible for free school meals (FSM) persistently underperform compared with peers in other ethnic groups, from early years through to higher education”.

Indeed, a recent survey by the Sutton Trust (3rd Nov 2022), conducted by academics from the Accent Bias in Britain project, has recently found that one in four have accents mocked at work: "The Sutton Trust found 46% of workers have faced jibes about their accents, with 25% reporting jokes at work. An entrenched "hierarchy of accent" caused social anxiety throughout some people's lives, researchers said. They said those with northern English or Midlands accents were more likely to worry about the way they spoke. Many of those who were mocked for the way they spoke admitted anxiety over their future career prospects because of perceived prejudiced attitudes" (report by BBC). As Sutton Trust Founder and Chairman, Sir Peter Lampl puts it: "I faced this myself when I was 11 years old. When I moved from Wakefield to Surrey, my broad Yorkshire accent stood out at my new school and resulted in me being mercilessly picked upon and ridiculed, and I learned to develop a Surrey accent in order to fit in. This is a common experience for those who are geographically or socially mobile. But this need not be the case" (Sutton Trust, 3rd Nov 2022).

Jamie Fahey in the Guardian (November, 2022) points out that "Too many people still face the prejudices I had to confront as a working-class Liverpudlian when I tried to become a journalist" and points out that "I had to fight my way through class barriers into my job" asking "Why has so little changed?". He points to the following evidence: "Consider the recent Social Mobility Foundation report on the social class pay gap, which found working-class employees were paid on average about £7,000 less than those from better-off backgrounds. It’s a colossal price to pay for the sheer circumstance of birthplace and family background. The price is higher for women, who face a pay gap of £9,500". Fahey concludes:

"I never did write as I speak: very few people actually do – but even back then, I understood the full thrust of that question. Perhaps it wouldn’t be asked that way today. The etiquette is different, but the assumptions remain intact. Sadly, so does the border".

The invention of personal computers in the 80s with spell checkers meant I could hide my slight dyslexia (which I wasn't aware of at the time) and put my computing background to work. My OCD helped me get organised and is, I found, I good trait for a researcher. Because I combined music, education and computing in my PhD I became interdisciplinary, and stayed that way. However, even in a well established interdisciplinary subject like Human Computer Interaction, researchers have problems getting the Computer Science mainstream to accept them. Computers and education stood no chance, at first any way, in fitting in with either Computer Science or Education. Academic work runs along tribal lines, no matter what the calls for grant proposals say. However, the explosion of human centered technology in general has challenged that. I managed to get extensive funding for the presentation of my research into human centred educational technology, as the academic travelogue above shows.

On the road

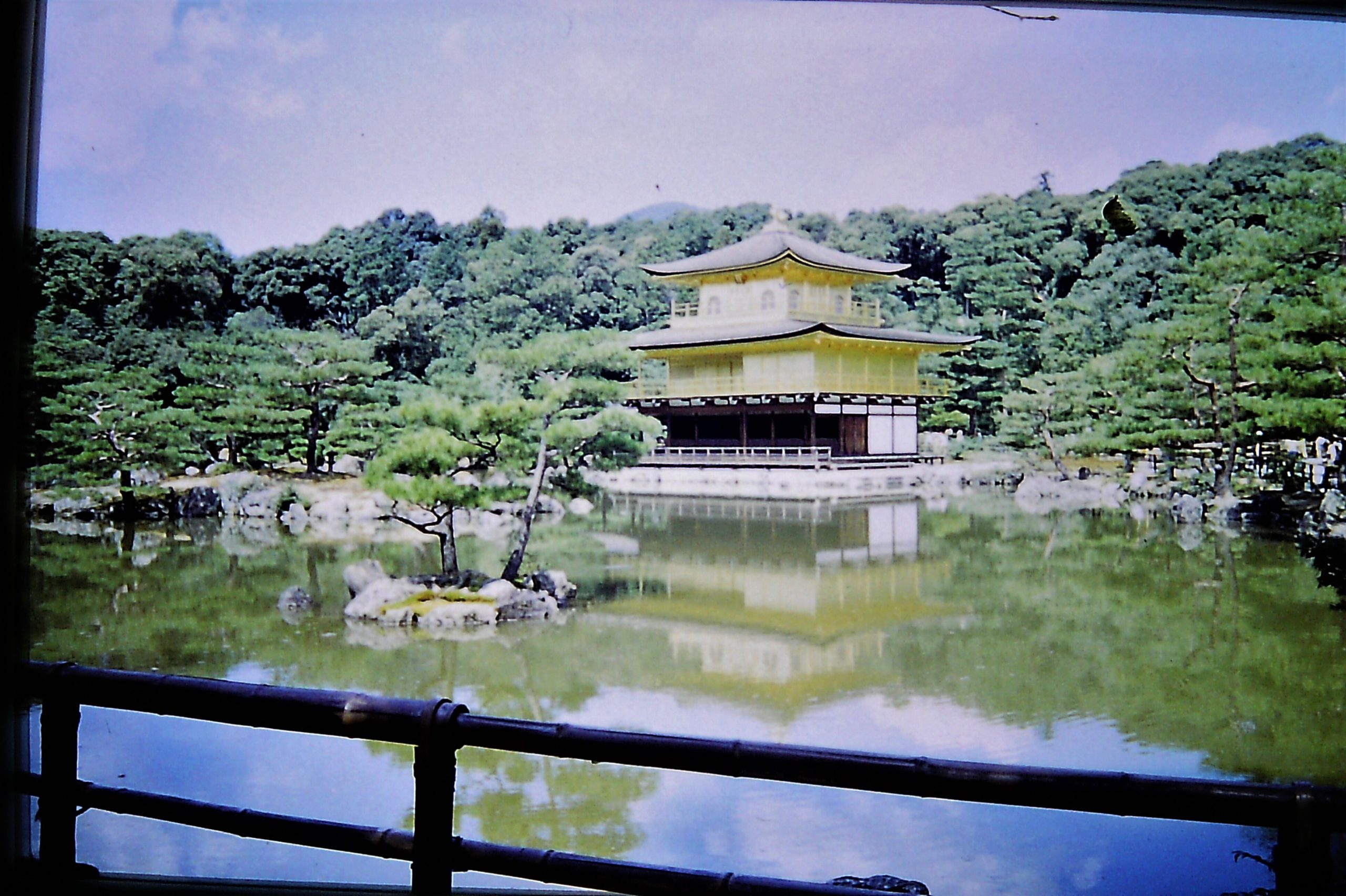

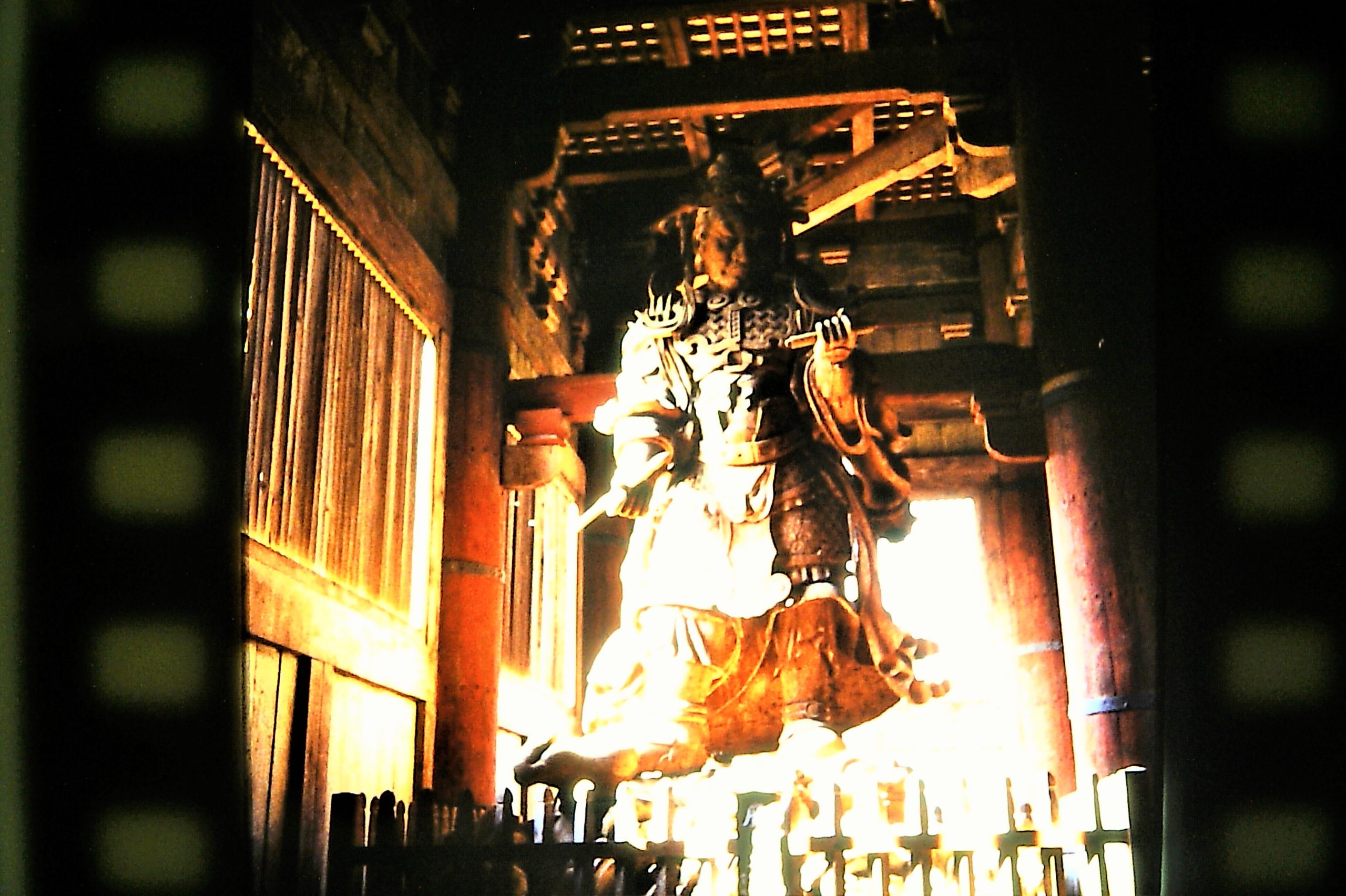

I was fortunate to visit Kobé, Japan, in 1997 to give a paper at a conference called AI-ED 97 (World Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Education). Following a peer review process, I was ranked in the top 5 papers. Whilst there I took the opportunity to visit Nara Park (all photos on this page), which has many amazing temples in it. All my photos were on 35 mm slides so I have rarely seen them over the past 24 years. So, I digitised them and am sharing them now; they look a bit like paintings, but I like them. Brilliant place. Some of the statues are really moody!

The conference paper, which was based on my PhD work, got invited for submission as a journal article, and after more reviews it was accepted: Cook, J. (1998). Mentoring, Metacognition and Music: Interaction Analyses and Implications for Intelligent Learning Environments. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 9(1-2), 45–87.

This work combined my three interests: education, music and computing.

Thank you to my Ex partner/wife Theresa Kinnison for supporting me at the time. Ditto to my PhD supervisors, first Mark Elsom-Cook, and significantly later on Michael Baker.

Privately educated still have ‘vice-like grip’ on most powerful UK jobs

Those in top roles are five times as likely to have been to private school than general population, study finds

Robyn Vinter North of England correspondent

The Guardian

Thu 18 Sep 2025

https://www.theguardian.com/society/2025/sep/18/private-schools-educated-most-powerful-jobs